Ed Lee has gone through a remarkable makeover in the last year, transformed from the mild-mannered city bureaucrat who reluctantly became interim mayor to a political powerhouse backed by wealthy special interests waging one of the best-funded and least transparent mayoral campaigns in modern San Francisco history.

The affable anti-politician who opened Room 200 up to a variety of groups and individuals that his predecessor had shut out — a trait that won Lee some progressive accolades, particularly during the budget season — has become an elusive mayoral candidate who skipped most of the debates, ducked his Guardian endorsement interview, and speaks mostly through prepared public statements peppered with contradictions that he won’t address.

The old Ed Lee is still in there somewhere, with his folksy charm and unshakable belief that there’s compromise and consensus possible on even the most divisive issues. But the Ed Lee that is running for mayor is largely a creation of the political operatives who pushed him to break his word and run, from brazen power brokers Willie Brown and Rose Pak to political consultants David Ho and Enrique Pearce to the wealthy backers who seek to maintain their control over the city.

So we thought it might be educational to retrace the steps that brought us to this moment, as they were covered at the time by the Guardian and other local media outlets.

Caretaker mayor

The story begins quite suddenly on Jan. 4, when the Board of Supervisors convened to consider a replacement for Gavin Newsom, who had been elected lieutenant governor but delayed his swearing-in to prevent the board from choosing a progressive interim mayor who might then have an advantage in the fall elections. Newsom and other political centrists insisted on a “caretaker mayor” who pledged to vacate the office after serving the final year of the current term.

It was the final regular meeting of the old board, four days before the four newly elected supervisors would take office. What had been a bare majority of progressive supervisors openly talked about naming former mayor Art Agnos, or Sheriff Michael Hennessey, or maybe Democratic Party Chair Aaron Peskin as a caretaker mayor.

When then-Sup. Bevan Dufty said he would support Hennessey, someone Newsom had already said was acceptable, the progressive supervisors decided to coalesce around Hennessey. That was mostly because the moderates on the board had suddenly united behind a rival candidate who had consistently said didn’t want the job: City Administrator Ed Lee.

Board President David Chiu was the first in the progressive bloc to breaks ranks and back Lee, saying that had long been his first choice. Dufty became the swing vote, and he abstained from voting as the marathon meeting passed the 10 p.m. mark, at which point he asked for a recess and walked down to Room 200 to consult with Newsom.

At the time, Dufty said no deals had been cut and that he was just looking for assurances that Lee wouldn’t run for a full term (Dufty was already running for mayor) and that he would defend the sanctuary city law. But during his endorsement interview with the Guardian last month, he confessed to another reason: Newsom told him that Hennessey had pledged to get rid of Chief-of-Staff Steve Kawa, a pro-downtown political fixer from the Brown era who was despised by progressive groups but liked by Dufty.

Chiu and others stressed Lee’s roots as a progressive tenants rights attorney, the importance of having a non-political technocrat close the ideological gap at City Hall and get things done, particularly on the budget. So everyone just hoped for the best.

“Run, Ed, Run”

The drumbeat began within just a couple months, with downtown-oriented politicos and Lee supporters urging him to run for mayor in the wake of a successful if controversial legislative push by Lee, Chiu, and Sup. Jane Kim to give million of dollars in tax breaks to Twitter and other businesses in the mid-Market and Tenderloin areas.

In mid-May, Pak and her allies created Progress for All, registering it as a “general civic education and public affairs” committee even though its sole purpose was to use large donations from corporations with city contracts or who had worked with Pak before to fund a high-profile “Run, Ed, Run” campaign, which plastered the city with posters featuring a likeness of Lee.

Initially, that campaign and its promotional materials were created by Pak (who refuses to speak to the Guardian) and political consultant Enrique Pearce (who did not return calls for this article) of Left Coast Communications, which had just run Kim’s successful D6 victory over progressive opponent Debra Walker, along with Pak protégé David Ho.

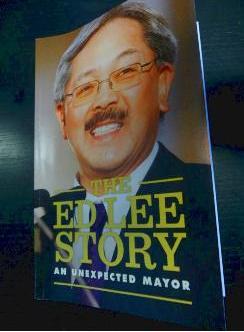

During that campaign, the Guardian and Bay Citizen discovered Pearce running an independent expenditure campaign called New Day for SF, funded mostly by Willie Brown, out of his office, despite bans of IEs coordinating with official campaigns. That tactic would repeat itself over the coming months, drawing criticism but never any sanctions from the toothless Ethics Commission. Pearce was hired by two more pro-Lee IEs: Committee for Effective City Management and SF Neighbor Alliance, for which he wrote the book The Ed Lee Story, a supposedly “unauthorized biography” filled with photos and personal details about Lee.

Publicly, the campaign was fronted by noted Brown allies such as his former planning commissioner Shelly Bradford-Bell, Pak allies including Chinatown Community Development Center director Gordon Chin, and a more surprising political figure, Christina Olague, a progressive board appointee to the Planning Commission. She had already surprised and disappointed some of her progressive allies on Feb. 28 when she endorsed Chiu for mayor during his campaign kickoff, and even more when she got behind Lee.

Olague recently told us the moves did indeed elicit scorn from some longtime allies, but she defends the latter decision as being based on Lee’s experience and willingness to dialogue with progressives who had been shut out by Newsom, noting that she had been asked to join the campaign by Chin. Olague also said the decision was partially strategic: “If we get progressives to support him early on, maybe we’ll have a seat at the table.”

Right up until the end, Lee told reporters that he planned to honor his word and not run. During a Guardian interview in July when we pressed him on the point, Lee said he would only run if every member of the Board of Supervisors asked him to, although about half the board publicly said that he shouldn’t, including Sup. Sean Elsbernd, who nominated him for interim mayor.

And then, just before the filing deadline in early August, Lee announced that he had changed his mind and was running for mayor, the powers of incumbency instant catapulting him into the frontrunner position where he remains today, according to the most recent poll by the Bay Citizen and University of San Francisco.

Lee the politician

With his late entry into the race and decision to forgo public financing and its attendant spending limits, one might think that Lee would have to campaign aggressively to keep his job. But most of the heavy lifting has so far been done by his taxpayer-financed Office of Communications (which issues press releases at least daily) and by corporate-funded surrogates in a series of coordinated “independent” groups (see Rebecca Bowe’s story, “The billionaires’ mayor”).

That has left Lee to simply act as mayor, where he’s made a series of decisions that favor the business community and complement the “jobs” mantra cited relentlessly by centrist politicians playing on people’s economic insecurities.

Yet Lee has been elusive on the campaign trail and to reporters who seek more detailed explanations about his stands on issue or contradictions in his positions, and his spokespersons sometimes offer only misleading doublespeak.

For example, Lee’s office announced plans to veto legislation by Sup. David Campos that would prevent businesses from meeting their city obligation to provide a minimum level of employee health benefits through health savings accounts that these businesses would then pocket at the end of the year, taking $50 million last year even though some of that money had been put in by restaurant customer’s paying 5 percent surcharges on their bills.

Although Campos, the five other supervisors who voted for the measure, four other mayoral candidates, and its many supporters in the labor and consumer rights movements maintained the money belonged to workers who desperately needed it to afford expensive health care, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce said it was about “jobs” that would be protected only if businesses could keep that money.

Lee parroted the position but tried to push the political damage until after the election, issuing a statement entitled “Mayor Lee Convenes Group to Improve Health Care Access & Protect Jobs,” saying that he would seek to “develop a consensus strategy” on the divisive issue — one in which Campos said “we have a fundamental disagreement” — that would take weeks to play out.

After a frustrating back-and-forth with Lee Press Secretary Christine Falvey by email, it’s still unclear how to resolve the contradiction between whether businesses could seize these funds or whether they belonged to employees, with her latest statement being, “The Mayor absolutely wants these funds spent on providing access to quality primary and preventative health care because this is the business’s obligation under HCSO. Making sure that these funds go to pay for health care is the most important objective.”

Similarly, when police raided the OccupySF encampment on Oct. 5, Lee’s office issued a statement that was a classic case of politicians trying to have it both ways, expressing support for the movement and its goal to “occupy” public space, but also supporting the need to police to clear the encampment of those same occupiers.

But now, in the wake of a repeat raid on Oct. 16 that has inflamed passions on the issue, the question is whether Lee can run out the clock and retain the office he gained on the promise of being someone more than a typical politician.