tredmond@sfbg.com

On July 24, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors weighed in on a policy debate that’s become a powerful cause on the American left. By a unanimous vote, the supervisors placed on the November ballot a measure calling for a Constitutional amendment to end corporate personhood.

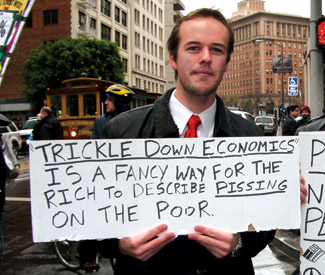

“We’re living in a time of trickle down economics and tax breaks for the rich,” Avalos said, later adding, “Big corporations [are] able to spend vast amounts of money” and have “the greatest influence on the outcome of elections.

“We need to look at our Constitution and have it amended so we aren’t looking at corporations as living, breathing people,” Avalos said.

That’s an immensely popular sentiment in this country, and it’s been stirred up by the US Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, a ruling that has come to represent all of the evils of big-money politics rolled into one two-word phrase.

More than 80 percent of Americans say they want the decision overturned. Six states, including California, have passed resolutions calling for a Constitutional amendment. Occupy protesters have made it a big issue. Marge Baker, policy vice president for People for the American Way, wrote a Huffington Post piece calling the campaign “A Movement Moment.”

But while Citizens United is a great rallying point, the challenge here goes way beyond one court decision. Citizens United didn’t create corporate personhood. Repealing the decision won’t end the flow of money in politics — and a lot of First Amendment experts are exceptionally nervous about anything that seeks to mess with this central part of the Bill of Rights.

And for all the denunciation of Citizens United, the solution — drafting the actual language of a new Constitutional amendment — turns out to be more than a little tricky.

MICHAEL MOORE AND HILARY CLINTON

Citizens United v. FEC has a complicated history. In 2002, Congress passed the McCain-Feingold Act, which barred corporations and unions from funding “electioneering” activities in the period right before an election.

The right-wing group Citizens United complained that Michael Moore’s documentary Fahrenheit 911 was an attack on George W. Bush and intended to influence the 2004 election, and the courts dismissed that complaint, saying that there was no evidence the independent documentary was an illegal campaign contribution.

Citizens United then started making its own “documentaries,” including one in 2008 that many saw as a campaign commercial against Hillary Clinton. The FEC found that the video was, in fact, “electioneering,” and the case wound up at the Supreme Court.

The legal decision was complicated, but among other things, the court ruled that a ban on independent corporate spending on election campaigns was a violation of the First Amendment rights of those business entities.

That was amplified when Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney uttered his famous line, “corporations are people.”

But in reality, Citizens United alone hasn’t caused the tsunami of big money that’s poured into elections, including the 2012 campaigns. Much of the cash contaminating the presidential coffers this year comes not from corporations effected by the ruling but from individuals and private trusts that have been free to throw money around for decades.

“The flood of money is disgusting and corrupting,” Peter Scheer, director of the California First Amendment Coalition, told us. “But it isn’t coming from public corporations. It’s mostly wealthy people and private trusts, and they didn’t need Citizens United to do this.”

In fact, the groundwork for modern sleaze was set a long time ago, in 1976, when the Supreme Court ruled in Buckley v. Valeo that, in effect, money was speech — and that any rich individual could spend all he or she wanted running for office.

What the Supreme Court has done, though, is set the modern political tone for campaign finance — among other things, invalidating a Montana law that barred corporate contributions to campaigns. And in the majority ruling and the assenting opinions, the court made clear that it doesn’t think government has any role in leveling the campaign playing field — that it’s not the business of government to decide that the money and speech of rich people and big business is drowning out the opinions and speech of the rest of the populace.

SO NOW WHAT?

So now that every decent-thinking human being in the United States agrees that there’s too much sleazy money in politics and that it’s not a good thing for government to be for sale to the highest bidder, the really interesting — and difficult — question comes up: What do we do about it?

There are a lot of competing answers to that question. And frankly, none of them are perfect.

That may be one reason why the ACLU is mostly on the sidelines. When I contacted the national office to ask if anyone wanted to talk about the efforts to overturn Citizens United, spokesperson Molly Kaplan sent me an email saying “we actually don’t have anyone available for this.”

But on its website, the organization — in a nuanced statement on campaign reform — notes: “Any rule that requires the government to determine what political speech is legitimate and how much political speech is appropriate is difficult to reconcile with the First Amendment.”

In an ACLU blog post, Laura Murphy, director of the group’s Legislative Office in Washington DC, argues that “a Constitutional amendment—specifically an amendment limiting the right to political speech—would fundamentally ‘break’ the Constitution and endanger civil rights and civil liberties for generations.”

But David Cobb, one of the organizers of Move To Amend, which is pushing a Constitutional amendment, told me that “the idea that spending money is sacred is part of the problem, the reason that we don’t have a functioning democracy.”

There are two central parts to the problem: The notion that corporations have the same rights to free speech as people, and the notion that money is speech. Eliminate the first — which is immensely popular — and you still allow the Meg Whitmans and Koch brothers of the world to pour their personal fortunes into seeking political office or promoting other candidates.

Eliminate the second and you open a huge can of worms.

“It would be a disaster, in my view,” Scheer said. “As a general principle, I’m frightened by the concept of tampering with the Constitution.”

Money may not equal free speech, but it’s hard to exercise the right to free speech in a political campaign without money. And there are broader impacts that might be hard to predict.

But Peter Schurman, one of the founders of MoveOn.org and a leader in Free Speech for the People, told me that “it’s a false premise that money equals speech. The point is to get a level playing field.”

THE PROPOSALS

Move to Amend and Free Speech for People are promoting similar approaches, Constitutional amendments that, in fairly simple terms, would radically and forever alter American politics. Several members of Congress have offered Constitutional amendments that include similar language.

The Move to Amend proposal is the broadest and cleanest. It states: “The rights protected by the Constitution of the United States are the rights of natural persons only. Artificial entities, such as corporations, limited liability companies, and other entities, established by the laws of any State, the United States, or any foreign state shall have no rights under this Constitution and are subject to regulation by the People, through Federal, State, or local law.”

It goes on to say: “Federal, State and local government shall regulate, limit, or prohibit contributions and expenditures, including a candidate’s own contributions and expenditures, for the purpose of influencing in any way the election of any candidate for public office or any ballot measure.”

It also includes this statement: “Nothing contained in this amendment shall be construed to abridge the freedom of the press.”

Free Speech for the People is simpler. It only addresses the corporate speech issue: “People, person, or persons as used in this Constitution does not include corporations, limited liability companies or other corporate entities established by the laws of any state, the United States, or any foreign state, and such corporate entities are subject to such regulations as the people, through their elected state and federal representatives, deem reasonable and are otherwise consistent with the powers of Congress and the States under this Constitution.”

Cobb notes that the Move to Amend measure doesn’t say how political speech should be regulated; it just opens the door to that kind of lawmaking. “The question of how to protect the integrity of the electoral process is a political question, not a Constitutional question,” he said. In the end, there’s a huge issue here. The framers of the Constitution, their political consciousness forged in a battle against big and repressive government, feared as much as anything the notion of rulers controlling the rights of the people to speak, write, assemble, publish (oh, and carry firearms) freely. Corporate interests (with the possible exception of the British East India Company, which monopolized the tea trade) weren’t a major concern.

And First Amendment purists still recoil at the idea that government, at any level, could make decisions limiting or regulating political speech. I sympathize. It’s scary. But in 2012, it’s easy to argue that the power of big money and big business has far eclipsed the power of government, that for all practical purposes, the rich and their corporate creations are the government of the United States — and that the people, assembled and exercising the power envisioned under the Constitution, need to make rules to, yes, level the playing field. Not rashly, not in crazy ways, with full cognizance of the risks — but also with the recognition that the current situation is fundamentally unacceptable, and that the potential dangers of messing with the First Amendment have to be balanced with the very real dangers of doing nothing.