arts@sfbg.com

Was Kunst-Stoff’s 15th anniversary concert this past weekend its last show in town? Perhaps, perhaps not. Yannis Adoniou, who founded the company with Tomi Paasonen, chooses his words carefully a couple of days before the shows. He acknowledges talking with local presenters about maybe “having an annual season here” and about “stabilizing our presence here.”

But for the time being, Kunst-Stoff is gone. The questions are “why?” and “why now?” In some ways, Adoniou has become a victim of his own success. He, together with La Alternativa and the Off Center, has run a successful studio space — the envy of many a struggling company — which has become what he calls a “sanctuary.” Besides classes and workshops the place has offered performance opportunities, not just for local artists but also for dancers from abroad like Anthony Rizzi and Constantine Baecher. “These conversations have been fantastic,” Adoniou says. “I could stay here as institutionalized Kunst-Stoff, but that’s what not what I am supposed to be doing. I have not done a major work in a theater for a long time because I have wanted to be available [to the artists working here].”

Adoniou, a ballet dancer originally from Greece, came to the Bay Area in 1993 after having seen Alonzo King set Without Wax on the Frankfurt Ballet. What impressed him was the equality between the sexes in King’s work. “I wanted to dance,” he remembers, and he knew that most ballet repertoire (at the time) reduced the male dancer to support the ballerina. He also liked that the Bay Area “does not have institutionalized names and technique as there are in New York and Europe.” So this was a good place for him as a young artist — but like many others, he finds it “very, very hard” to get support once you have developed beyond a certain level. So back to Europe it is, where he feels he can take his own work where it needs to go.

The easy riding 98-13, the second of the three pieces which formed the 15th anniversary retrospective, offered a good overview of Adoniou’s perspective on dance. He has long passed the restrictions of his ballet training not be rejecting but by transcending it. Some of 98-13’s individual moments did ring a bell — Repetika, Less Sylphides, the moment you stood — but for the most part they toppled over each other as if spilled from a bag of toys. This was an affectionate, lighthearted look at the past.

The fun was in seeing the dancers take shape. Leyya Tawil resembled a huge bird on the tip of her toes. Daiane Lopes da Silva is a fierce mover but also a comedian. Katie Gaydos told us that giving birth is no more difficult than doing a rond de jambe en l’aire. I’ll take her word for it. Parker Murphy, as the only male, of course got to lift some obstreperous females. In the end, Adoniou, in a business suit, offered an intricate, determined walking combination that included a lovely arabesque. Maybe he was taking measure of what has passed, or perhaps of what lies ahead.

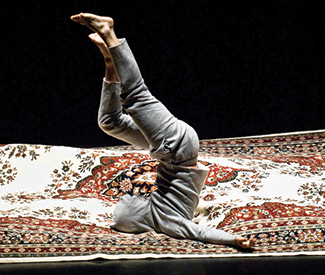

If 98-13 was full of surprises, the trajectory for the opening Solo for Yannis could be foreseen. Strongly danced by Lopes da Silva with the assistance of Widon Yang, Ivo Serra, and Tomi Paasonen, the piece posed questions about navigating unstable ground if you have no point of reference. Blinded by a hooded garment, she rolled, stretched, and recoiled on a rug that kept being yanked away, her fingers becoming antennas, her head sniffing the air. Precarious for the men and the dancer, Solo derived its interest from the tiny shifts of give and take, limitations set and rejected. The moral of this story? Keep going even if you end up being naked, vulnerable, and alone.

Paasonen’s ironically named Those Golden Years may have been inspired by a dream about his mother but it also threw a mirror at Adoniou. The work opened with composer Yuko Matsyama, a flower garden in motion, carefully tracing a path along the edge of a mound of what turned out to be crumpled sheets of gold and silver Mylar. Her rhythmically intriguing score, which included a narration by Paasonen, set the tone for what became a seductive, but also touching visual feast.

Predictably, Adoniou emerged from this heap of plastic — one limb at a time. Yet Golden’s airy, glittering artifice contrasted seductively with the solidity and warmth of the human body. The dancer smashed, admired, hugged, and hid in it. He donned it as a fairy prince’s garment but also as a garbage bag. Eventually he too was left naked — even deprived of his manhood. *