joe@sfbg.com

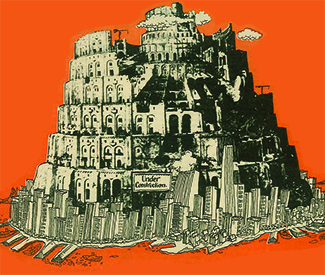

The housing crisis is spurring pro-development arguments that threaten to hasten the “Manhattanization of San Francisco,” a buzzphrase from another era that led to local controls on high-rise development.

The city is getting richer and less diverse, and the unaddressed displacement of longtime residents has fueled populist outrage. Now, politicians are finally getting the message, but some are offering solutions that may reopen old civic wounds.

They say that the answer to the housing affordability crisis is to build massive amounts of new housing, and to build it higher and more densely than city codes and processes currently allow.

Sup. Scott Wiener wrote a scathing indictment of the city’s alleged aversion to housing production in the San Francisco Chronicle on Jan. 13, slamming a planning process that he says slows necessary construction.

“This disconnect — saying that we need more housing while arbitrarily finding reasons to kill or water down projects that provide that housing — is having profound effects on our city and its beautiful diversity, economic and otherwise,” Wiener wrote.

Though he mentioned affordable housing, the need to build all kinds of housing was the crux of his argument. It’s the same kind of developer-friendly rhetoric that whips people into a frenzy with faux common sense: build more, and the market will take care of everyone.

But there are flaws to that simplistic argument. Housing advocates (and Guardian editorials) have long argued that market rate units — the median price of which just surpassed $1 million — don’t trickle down to maintain the city’s economic diversity. More supply may help, but with insatiable demand for housing here, it won’t help much with affordability for the working class.

The next day, Wiener introduced legislation to loosen density requirements when developers build below-market-rate housing units on site, creating an incentive to build more of the units that affordable housing advocates say are most valuable.

“Long term, I’m concerned about young persons that can come here,” he told the Guardian. “It’s not just about building more housing.”

Pushing a pro-development agenda while playing lip service to an affordable housing push is all the rage in San Francisco nowadays, with Mayor Ed Lee calling for building 30,000 new housing units by 2020, supporting the rapid growth calls by SPUR, Housing Action Coalition, and other pro-growth groups.

But Peter Cohen, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, says supply and demand logic doesn’t apply to the San Francisco housing market for a number of reasons.

He pointed to a paper by CCHO cohort Calvin Welch, who teaches a class on the politics of housing development at USF and SFSU. Welch cites data from the City Controller’s Office showing that when San Francisco increases supply, the market responds by raising the average housing price. Contrary to all the supply and demand claims, when we produce more, things get more expensive.

Why?

“In classic economic theory prices are set by supply and demand only when the market is ‘competitive’ when neither consumers nor suppliers have the ‘market power’ to set the price by themselves,” Welch wrote. “Clearly, that is not the case in San Francisco…of the City’s 47 square miles, only 13 square miles is available for housing uses.”

“There is no ‘free land’ in San Francisco,” he wrote. “The owners have total ‘market power’ over its price.”

But that’s the kind of complex argument that has a tough time penetrating the public consciousness. The idea isn’t as catchy as “supply and demand.”

“I think frankly this whole thing about build, build, build — it’s an easy answer to something that’s complex,” Cohen told us. “It resonates. It sounds like the easy path to sound like you know what you’re talking about.”

That simplistic thinking is dangerous, though, because San Francisco is quickly becoming Manhattanized. Since 2002, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg rezoned over 37 percent of New York City, according to The New York Times, causing the construction frenzy many are seeking for San Francisco.

Bloomberg added 40,000 buildings in his time as mayor, but that boom had mixed results. It arguably hastened the Big Apple’s gentrification, especially in Manhattan, one of the few US locales denser than San Francisco.

From 2000 to 2010, Manhattan’s ranks of white people swelled by 58,000. During the same period, the wealthy home of Wall Street lost 29,000 African Americans and 14,000 Latinos. More alarming is the income disparity there.

From 1990 to 2010, the city that never sleeps, and its neighborhoods, increasingly became a land of have and have-nots. Census maps showed that while 1990 Manhattan had economic diversity, now the median income hovers over $75,000 for most blocks of that famous borough.

Articles from the Times and NYC-based housing advocacy organizations frequently describe Manhattan as a haven of wealthy white yuppies. Sound familiar?

San Francisco is quickly following suit. The same census maps that show the swell of wealth in Manhattan show a swell of wealthy folk in San Francisco.

BMR housing set-asides help, and Mayor Lee has promised to ramp up BMR production, calling for about 10,000 units by the year 2020. But any serious increase in housing production carries its own cost in a city where public transit and other vital infrastructure are already underfunded and would need serious new investments.

In his Jan. 17 State of the City speech, Mayor Lee warned against demonizing the tech industry or with pitting one group against another. “San Francisco changes us more than any group of newcomers will change San Francisco,” he said to the invite-only crowd.

The difference now is the wealth that threatens to gentrify San Francisco’s weird soul, the one we’ve hung onto since a man named Joshua Norton declared himself Emperor of the United States and was hailed as a San Franciscan icon.

“Manhattanization” is not just a buzz term or a scare tactic: It’s representative of a specific set of zoning and construction policies that many San Franciscans are now advocating for, which will change the demographics and politics of this city, whether we like it or not.

San Francisco’s chief economist addresses supply and demand in terms of housing — it’d take over 100,000 new housing units to make a dent in housing prices in San Francisco.