It was more than six years ago that Jeanne Hardebeck, a seismologist at the US Geological Survey’s Menlo Park Earthquake Science Center, started to zero in on a pattern. “I was looking at small earthquakes,” she explained. “I noticed them lining up.”

She and other earthquake scientists also detected an anomaly in the alignment of the earth’s magnetic field off the California coastline, near San Luis Obispo. It all added up to the discovery of an offshore fault line.

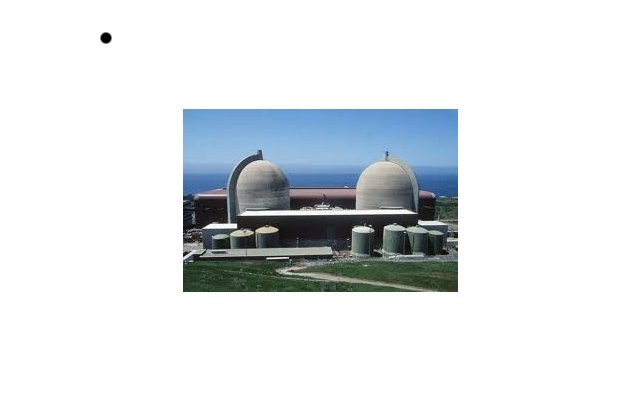

What made Hardebeck’s discovery truly startling was that the sea floor fracture, now known as the Shoreline Fault, lies just about 300 meters from Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, California’s last operational nuclear power plant. In the general vicinity of the facility, which is owned and operated by Pacific Gas & Electric Co., there are also three other fault lines.

These discoveries have raised safety concerns and fed arguments by activists who want the Diablo Canyon reactors shut down, at least until the danger can be properly assessed.

When the final construction permits for Diablo Canyon were issued more than 45 years ago, engineers assumed a lower seismic risk. PG&E’s federal operating license to run Diablo Canyon is based on those assumptions. But the new information suggests that the ground is capable of shaking a great deal more in the event of a major earthquake than previously understood — leaving open the possibility that a temblor could spark sudden and disastrous equipment failure at Diablo Canyon.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the federal agency charged with overseeing the safety of nuclear facilities, has determined that the plant’s continued operation is safe. But Michael Peck, a senior NRC staff member, recommended that the reactors be shut down until a safety analysis could prove that the plant would successfully withstand a major earthquake. In the time since Peck began to sound the alarm about the potential seismic hazard, he’s been transferred from Diablo Canyon to a NRC training facility in Chattanooga, Tenn.

As The Associated Press reported on Aug. 25, Peck, who served as a resident on-site safety inspector at Diablo Canyon for half a decade as part of his 33-year career with the NRC, called for the plant to be temporarily shut down in a Differing Professional Opinion (DPO) filed in June 2013. Such a filing signifies a formal challenge to an agency position, and the NRC standard is to rule on these findings within 120 days.

More than a year later, however, Peck’s findings still haven’t been addressed. Since the DPO is technically classified — someone leaked it, and Peck says he wasn’t the source —the NRC hasn’t even publicly acknowledged its existence. The NRC did not return calls seeking comment.

Meanwhile, the Bay Guardian has learned that the NRC’s actions go beyond just foot-dragging on addressing Peck’s findings. Following a series of exchanges in the years since the discovery of the Shoreline Fault, PG&E filed a request to the NRC for its license to be amended so that it could continue operating Diablo Canyon in spite of the outmoded design specifications. As part of its request, the company performed its own studies concluding that the continued operation of the plant was safe in light of the new seismic information.

Yet the NRC technical staff rejected PG&E’s proposed methodology for analyzing the earthquake safety risk. Rather than amend the license, the NRC asked PG&E to withdraw its request. Despite this formal response, in a letter dated Oct. 12, 2012, an NRC project manager quietly gave PG&E the green light to update its own safety analysis report to incorporate the new seismic information, effectively allowing for the amendment without jumping through the hoops of the formal license amendment process.

“It appears that the licensing manager basically worked around the process,” Peck told us. Asked why he thought something like that might happen, he said, “I think there’s a prevailing viewpoint that … the plant is robust, and that even though it doesn’t meet its license requirements, it’s safe.” Nevertheless, “when our technical reviewers did a detailed review of the actual methodology, they said, we can’t approve it. It’s beyond what we can approve. I think that surprised a lot of people.”

Peck explained that the safety evaluations assess whether power plant equipment can be expected to remain “operable” in the event of an earthquake, in accordance with the agency’s technical standards. “In my opinion, their evaluation didn’t meet the standard,” he said.

That’s what prompted him to file two objections to the NRC’s decision to continue operating the facility despite the looming safety concerns. Peck stressed that he could not discuss the DPO, since it’s not a public document, but did speak about the concerns he raised in his first objection, which is publically available.

Peck emphasized that while he wasn’t saying outright that Diablo Canyon is unsafe, having the safety concerns out there as an unresolved question is unacceptable.

“How much will the plant shake? There’s not a clear consensus,” he told us.

When he performed his own analysis, concluding that PG&E’s evaluation wasn’t adequate, he based his assumptions on PG&E’s seismic calculations. Even by those numbers, which aren’t universally accepted, the peak ground acceleration in the event of an earthquake is “almost double” what PG&E’s operability standard is based on. PG&E did not return calls seeking comment.

Hardebeck, the seismologist, said that while the engineering questions are a point of contention, there’s little dispute about the earthquake science. “An earthquake on any one of these faults is very rare,” Hardebeck noted. The Shoreline Fault, for example, has an expected probability of rupturing in a major earthquake — of magnitude 6.5 or 6.7 — once every 10,000 years.

However, the existence of numerous fault lines in proximity means that if one ruptured, more earthquakes could be triggered along the other fault lines.

“It was only in the 1970s that some geologist found the Hosgri Fault — which turns out to be the biggest fault in the region,” Hardebeck said. “The Shoreline is sort of a little strand of the Hosgri Fault,” she added.

Seismologists predict that the Hosgri Fault could trigger a large earthquake, up to magnitude 7.5, once every 1,000 years. Also near Diablo Canyon are the Los Osos and San LuisBay faults, which Hardebeck said aren’t as well-understood by seismologists but could potentially rupture and cause earthquakes of a 6.5 magnitude.

Dave Lochbaum, who worked at the NRC prior to his current position at the Union of Concerned Scientists, provided some perspective by pointing out that nobody had expected the natural disaster that triggered the Fukushima nuclear meltdown in Japan in March 2011.

“For context, the odds of a tsunami wave exceeding the protecting sea wall was one in 3,480 years,” he noted. “You’re in the same ballpark.”

Lochbaum said the Union of Concerned Scientists agreed with Peck’s analysis on Diablo Canyon. “He believes in nuclear power,” Lochbaum pointed out. “He’s not trying to say this plant can never split another atom. This plant is outside those rules and it needs to be fixed. … Technically, the plant has no legal basis for operating.”

The day after the AP article was published, the environmental nonprofit organization Friends of the Earth filed a 92-page petition with the NRC, calling for the Diablo Canyon to be shut down.

“Since Diablo is not operating within its licensing basis, as Peck asserted, the plant must suspend operations while the NRC considers a license amendment,” its petition states.

Yet by subverting the formal license amendment, as NRC public records show, the regulatory agency effectively skipped over a public process with an adjudicatory hearing that would have allowed concerned citizens to weigh in.

In the days following the AP report, US Sen. Barbara Boxer said she would submit a hearing request at the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee to ask the NRC about the matter. But aside from the checks and balances provided by the Senate and congressional oversight committees, the NRC is “the only game in town” when it comes to determining whether Diablo Canyon should continue operating or be shut down, said Lochbaum, who worked as a nuclear engineer for 17 years.

In a blog posted on the Union of Concerned Scientists website, Lochbaum said he had researched the history of how the NRC had treated similar situations.

“In all prior cases, I found that the NRC did not allow nuclear facilities to operate with similar unresolved earthquake protection issues,” he wrote. “For example, in March 1979 —two weeks prior to the Three Mile Island accident — the NRC ordered a handful of nuclear power reactors to shut down and remain shut down until earthquake analysis and protection concerns were corrected. Thus, Dr. Peck’s findings are irrefutable and his conclusion consistent with nearly four decades of precedents. What is not clear is why DiabloCanyon continues to operate with inadequately evaluated protection against known earthquake hazards.”